Table of Contents

Introduction to Pneumatics and Why They Matter

Pneumatics, or the study and application of pressurized air to create mechanical motion, form the backbone of countless machines and processes. From factory automation to dental drills, pneumatic systems harness the energy of compressed air to produce linear or rotational movement. Compressed air has been used for centuries, but modern pneumatics integrate filters, regulators, valves, actuators and electronic control to create precise and reliable motion. Understanding how pneumatics work and where they excel is essential for engineers, designers, and sourcing specialists seeking efficient, cost‑effective and durable solutions for motion control. In this guide, every paragraph will reinforce the focus on pneumatics to ensure clarity for search engines and human readers.

Modern pneumatics rely on a simple principle: store energy by compressing air, release it to perform work, then exhaust or recycle the air. An air compressor draws in atmospheric air and compresses it to a higher pressure. Filters remove moisture and particulates, regulators keep pressure constant, valves direct flow, and actuators such as cylinders convert air energy into motion. Because pneumatics use air rather than hydraulic oil, they are inherently clean and safe, leaks simply release air rather than hazardous fluids. This inherent safety has made pneumatics popular in food packaging, medical devices and other hygiene‑critical industries. Throughout this article, we will explore the components, advantages, design considerations and emerging trends that define modern pneumatics.

How Pneumatics Work — Components and Architecture

Pneumatic systems consist of five main subsystems: air generation, air preparation, distribution, control and actuation. Each subsystem contributes to the overall performance and reliability of pneumatics.

- Air Generation — Every pneumatic system starts with an air compressor. Compressors intake atmospheric air and increase its pressure. They come in piston, rotary screw, scroll and vane styles. The compressed air output must meet the pressure and flow demands of downstream components.

- Air Preparation — Before compressed air can be used, it must be cleaned and conditioned. Filters remove water vapor and particulates; regulators maintain consistent pressure; lubricators inject oil into the air stream if required. Proper air preparation is vital to prevent premature wear and sticking of valves and actuators.

- Distribution — Tubing, hoses and fittings distribute air through the system. Tubing materials include polyurethane, polyethylene, nylon and PTFE, each chosen for flexibility, chemical resistance or temperature capability. Fittings connect tubes to valves and cylinders; the push‑to‑connect style is common for quick installation.

- Control — Valves control the direction, rate and timing of air flow. Directional control valves determine whether air goes to an actuator or exhaust. Flow control valves regulate speed, check valves ensure one‑way flow, and pressure regulators maintain set pressure. Valve actuation may be manual, mechanical, pneumatic or solenoid‑driven. Control architecture defines the responsiveness and precision of the pneumatic system.

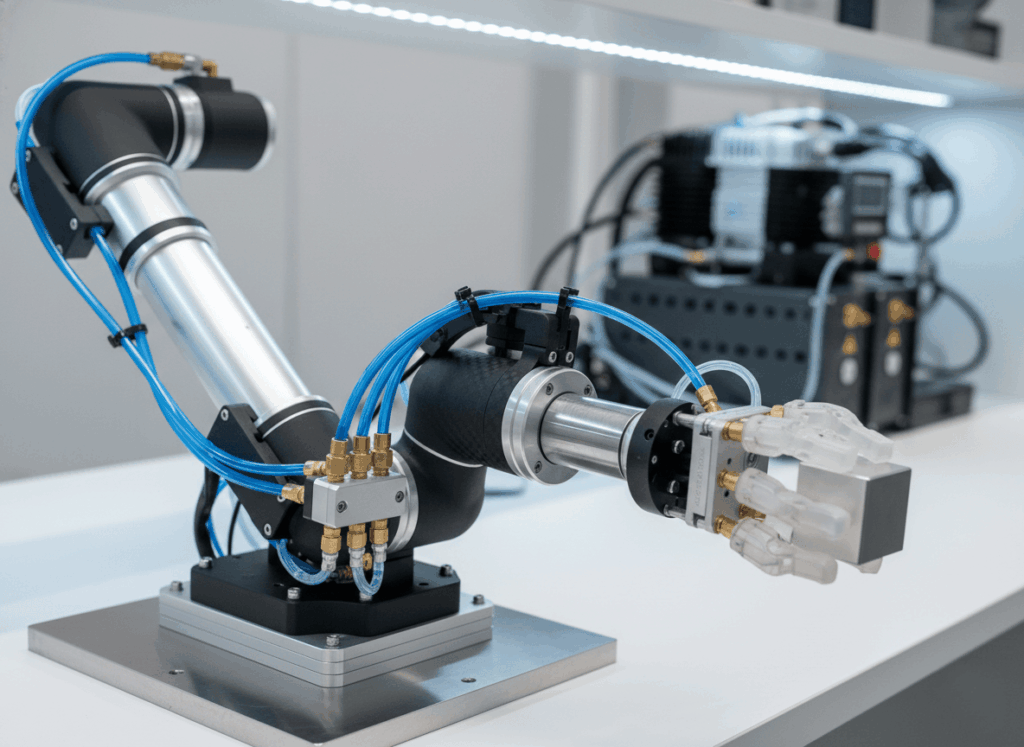

- Actuation — Actuators convert compressed air into motion. The most common actuators are cylinders that provide linear motion. Rotary actuators, grippers, and vacuum ejectors offer additional forms of movement. The design of the actuator, single‑acting, double‑acting, rodless, ISO or guided, affects the performance and suitability for specific tasks.

Pneumatics bring these subsystems together to create nimble and responsive machines. By adjusting air pressure, valve timing and cylinder size, designers can tailor performance for tasks ranging from delicate assembly to high‑speed pick‑and‑place operations. In the following sections, we will unpack each element to demystify pneumatics.

Advantages of Pneumatics Compared to Hydraulics and Electromechanical Systems

Pneumatics possess unique advantages that make them attractive in industry. Relative to hydraulics, which use incompressible oil at high pressures (often 1,000–5,000 psi) and require elaborate leak containment, pneumatics operate at lower pressures (typically 80–100 psi) and produce cleaner operation because escaping air does not cause contamination. This advantage makes pneumatics ideal for food processing and medical equipment where cleanliness is paramount.

Another advantage of pneumatics is simplicity and durability. Pneumatic devices often have fewer moving parts and simpler designs compared with electric motors or hydraulic cylinders. According to JHFOSTER, pneumatic systems are easy to design and adapt to harsh environments, have high durability and long life, and are cost‑effective in both installation and maintenance. Because air is compressible, pneumatic systems can tolerate sudden stops and slight leaks without catastrophic failure. Pneumatics also perform well in explosive or flammable environments since they do not use combustible fluids.

Speed and responsiveness further differentiate pneumatics. Compressed air flows quickly through pipework and can change direction rapidly, giving pneumatic systems high speed compared to hydraulics. Reaction times on the order of milliseconds allow pneumatics to excel in rapid pick‑and‑place and high‑cycle automation. Air springs provide shock absorption and cushioning, contributing to smooth motion. Light weight is another benefit; pneumatic cylinders often weigh less than comparable hydraulic cylinders and do not require heavy pumps or reservoirs.

From a cost perspective, pneumatics are generally affordable. Compressors and air preparation equipment can service many devices simultaneously, and maintenance is straightforward. The JHFOSTER article notes that pneumatics offer high effectiveness and are cost‑efficient compared with electrical and hydraulic systems, though accuracy may be lower. For tasks where extreme precision or high force is not necessary, pneumatics offer an excellent balance of performance and cost.

Despite these advantages, pneumatics have limitations. Force output is lower than hydraulics because air’s compressibility limits maximum pressure. According to Rowse, hydraulic systems can produce pressures up to 5,000 psi while pneumatics typically operate around 80–100 psi. This means hydraulics are better suited for heavy lifting and pressing applications. Another limitation is energy efficiency; compressors must run continuously to maintain pressure, and air leakage can reduce efficiency. Additionally, precise positioning is harder to achieve due to air compressibility and potential for pressure drops. Engineers must consider these trade‑offs when selecting between pneumatics and other actuation methods.

Key Pneumatic Actuators: Cylinders and Their Variants

Cylinders remain the heart of many pneumatic systems, converting the pressure of compressed air into useful linear or rotary motion. Understanding the types of cylinders and their functions is crucial for effective design and selection.

Single‑Acting Cylinders

Single‑acting cylinders use compressed air to create motion in one direction. A spring or external force returns the piston to its original position when air is released. These cylinders are simple, inexpensive and ideal for applications where force is required only in one direction, such as clamping or ejection mechanisms. However, the spring limits stroke length and may fail under high cycle rates. Because return force depends on spring strength, the reverse stroke may not be as controlled or powerful. In most paragraphs about pneumatics, single‑acting cylinders represent a common starting point for design.

Double‑Acting Cylinders

Double‑acting cylinders apply air pressure to both sides of the piston, providing force in both directions. They consist of a cylindrical barrel, piston, rod and end caps with seals to separate the chambers. Double‑acting cylinders offer precise control, consistent speed and equal force in both directions. They are widely used in robotics, packaging, automation and other applications requiring bidirectional motion. Because they consume compressed air during both extension and retraction, they require greater air supply than single‑acting cylinders. Designers must ensure adequate compressor capacity and consider energy consumption in pneumatic systems using double‑acting cylinders.

Rodless Cylinders and Guided Actuators

Rodless cylinders provide linear motion without a protruding rod. Instead, the piston is connected to a carriage that travels along the cylinder body through a magnetic or mechanical coupling. This arrangement saves space and protects the moving mechanism from external contamination. Rodless cylinders come in magnetically coupled and mechanically coupled designs, enabling long strokes up to several meters. They are ideal for material handling, conveyor systems and sliding doors. Guided cylinders incorporate external guide rods or carriages to control side loads and ensure precise alignment. For example, ISO guided cylinders combine standard cylinder tubes with parallel guide rods and bearings to provide stable linear motion in pneumatics.

Rotary Actuators and Grippers

While linear motion dominates pneumatics, rotary actuators convert compressed air into rotational movement. Vane‑type, rack‑and‑pinion and piston‑driven rotary actuators produce arcs ranging from a few degrees to multiple turns. Applications include indexing tables, valve positioning and clamp rotation. Pneumatic grippers use parallel or angular jaws driven by small cylinders to grasp objects; they are common in pick‑and‑place robotics. In the context of pneumatics, rotary actuators and grippers extend the versatility of compressed air systems beyond simple linear motion.

ISO Standard Cylinders and Specialized Designs

ISO cylinders conform to international standards (e.g., ISO 15552 for tie‑rod and profile cylinders). Standardization simplifies sourcing and interchangeability because cylinders from different manufacturers share mounting dimensions. ISO cylinders are available in various bore sizes and strokes, with options for adjustable cushioning and magnetic pistons for sensor feedback. Specialized cylinders include rodless, guided, compact and cleanroom variants. Compact cylinders have short strokes and small footprints for tight spaces. Cleanroom cylinders use low‑friction seals and stainless‑steel housings to prevent particle generation. Understanding these variants allows designers to choose the right pneumatic cylinder for specific applications.

Selecting Pneumatic Cylinders — Practical Guidelines

Choosing the right cylinder requires balancing force, speed, space and environmental constraints. These guidelines help ensure that pneumatics deliver the intended performance.

- Calculate Required Force — The force produced by a cylinder equals air pressure multiplied by piston area, minus friction. Determine the load to be moved and account for friction and safety factors. The Tameson selection guide emphasizes considering bore size, pressure and load to ensure adequate force.

- Choose Bore Size — Larger bores produce greater force but consume more air and occupy more space. Use the smallest bore that meets force requirements to minimize air consumption and optimize pneumatics efficiency. If a job demands high force, consider using hydraulics instead.

- Determine Stroke Length — The stroke must match the required travel plus allowances for cushioning and mechanical tolerances. Avoid using the full stroke to prevent piston impact on end caps. For long strokes, rodless cylinders may be more appropriate, particularly when space is limited.

- Select Cylinder Type — Decide between single‑acting and double‑acting based on whether force is needed in one or both directions. For space‑saving, choose rodless or compact cylinders. For high accuracy, select guided cylinders with anti‑rotation features.

- Choose Mounting Style — Mounting affects alignment, load distribution and maintenance. Common styles include front flange, rear flange, clevis, trunnion and foot mounts. Ensure the mounting supports the cylinder’s weight and load without introducing bending moments.

- Consider Speed and Cushioning — Pneumatic speed depends on air flow and valve size. Flow control valves restrict exhaust or inlet flow to regulate speed. Cushioning mechanisms absorb kinetic energy near stroke end to prevent impact and reduce noise. Adjustables include pneumatic cushions and shock absorbers.

- Evaluate Environment — Temperature, dust, moisture and chemical exposure influence cylinder materials and seals. Stainless steel cylinders resist corrosion, while aluminum is lightweight but less durable. Choose seals suitable for high temperatures or aggressive chemicals when necessary.

By following these guidelines, engineers can select the optimal pneumatic cylinder. Using these best practices ensures that pneumatics deliver consistent motion and long service life.

Understanding Pneumatic Valves — Directing Air with Precision

Valves serve as the brains of pneumatic systems, directing air to actuators, venting exhaust and controlling speed. Several valve families exist, each with unique characteristics and uses.

Directional Control Valves

Directional control valves route air to different ports based on their configuration. Common designations include 2/2, 3/2, 4/2 and 5/2, where the first number represents the number of ports and the second number represents positions. A 3/2 valve has three ports (supply, actuator and exhaust) and two positions (closed or open). 5/2 valves have five ports: two actuator ports, one pressure supply and two exhaust ports, enabling independent exhausts for each actuator port. According to Tameson, 5/2 valves offer separate exhaust paths, while 4/2 valves combine exhausts and are often used for double‑acting cylinders. Choosing between these depends on whether independent exhaust control is needed.

Actuation Methods: Manual, Mechanical, Pneumatic and Solenoid

Valves can be actuated manually (lever, push button), mechanically (roller or cam), pneumatically (pilot pressure) or electrically via solenoids. Solenoid valves convert electrical signals into magnetic force to shift the valve spool or poppet. Mono‑stable valves return to a default position when the actuation signal stops, while bi‑stable (latching) valves maintain their state until the opposite signal is applied. Pilot‑operated valves use a smaller pilot valve to control a larger main valve, reducing the required power and coil size. In modern pneumatics, solenoid valves integrate seamlessly with PLCs and fieldbus networks for precise digital control.

Spool vs. Poppet Valves

Two common directional valve designs are spool and poppet. Spool valves contain a sliding cylindrical element with O‑rings that opens or closes ports; they are versatile and suitable for vacuum applications. Poppet valves use a sealing element pressed against a seat by a spring; they provide fast response, high flow, low leak rates and long life, especially when used with clean, dry air. Poppet valves handle high cycling with minimal wear and are often chosen for high‑speed or harsh environments. In pneumatic systems where leak‑tight operation and quick response are critical, poppet valves deliver superior performance.

Solenoid Valve Port Configurations: 5/2 vs. 4/2

As noted earlier, 5/2 and 4/2 solenoid valves differ in port count and exhaust handling. A 5/2 valve typically uses two solenoids or one solenoid with a spring to shift between two positions, providing independent exhausts for each actuator port. A 4/2 valve may use one solenoid and a spring to return to the default position, venting both actuator ports through a single exhaust port. Tameson notes that 5/2 valves are preferred when separate exhaust ports reduce cross‑contamination or when dual control is needed, whereas 4/2 valves are simpler and often adequate for standard double‑acting cylinders. In pneumatics, understanding these differences helps designers select the correct valve for control precision and system cleanliness.

Valve Sizing and Response

Valve sizing determines flow capacity, response time and energy consumption. A valve that is too small restricts flow and slows cylinder speed, while an oversized valve wastes air. Many manufacturers publish flow curves in terms of Cv or Kv values. Designers should calculate required flow based on cylinder volume, cycle rate and pressure drop. Response time is influenced by spool weight, spring force and solenoid coil strength. High‑speed pneumatics demand valves with fast switching times, on the order of milliseconds. Poppet valves often provide faster response than spool valves due to their simple geometry. By tuning valve selection, pneumatics can achieve the desired balance of speed, precision and energy efficiency.

Pneumatic Fittings and Tubing — Making Reliable Connections

Fittings and tubing may seem like secondary details, but they determine the integrity and performance of pneumatic systems. Poor connections lead to leaks, pressure drops and inefficiency. Understanding fitting types, materials and selection criteria is critical to building reliable pneumatics.

Types of Fittings

• Push‑to‑Connect (or Instant) — These fittings allow tubing to be inserted and locked without tools. A collet grips the tube while an O‑ring seals the connection. Push‑to‑connect fittings speed assembly and maintenance, making them popular for general industrial pneumatics.

• Compression Fittings — These fittings consist of a nut and ferrule that compress onto the tubing when tightened, providing a secure and often reusable connection. Compression fittings are used in applications requiring high pressure or where vibration is present.

• Barbed Fittings — Barbed fittings have ridges that grip flexible hose. Hose clamps or crimp sleeves secure the hose. They are economical but may not be as easy to install or remove as push‑to‑connect fittings.

• Quick Disconnect Couplings — Couplings allow rapid connection and disconnection between hoses or tools. They often incorporate a valve that shuts off flow when disconnected to prevent air loss. Safety couplings include features to bleed pressure before separation.

• Threaded Adapters — Threads such as NPT, BSPT, BSPP (G), metric and straight threads enable connection to valves, cylinders and manifolds. Teflon tape or thread sealant ensures leak‑free joints. Awareness of thread standards prevents cross‑threading and leaks.

Fitting Materials and Selection Criteria

Material choice affects corrosion resistance, weight and cost. Common materials include brass (affordable and corrosion‑resistant), stainless steel (excellent corrosion resistance in harsh environments), aluminum (lightweight but less durable), and plastic composites (lightweight and corrosion‑proof for food and water applications). When selecting fittings, consider:

- Tube or Hose Type — Match the fitting to the tubing material and outer diameter. Polyurethane and nylon tubes are common in pneumatics, while PVC or rubber hoses may be used for high flexibility or exposure to chemicals.

- Pressure Rating — Ensure fittings meet or exceed the system’s maximum working pressure. Compression fittings often have higher pressure ratings than push‑to‑connect fittings.

- Thread Compatibility — Use the correct thread standard for each component. Mixing NPT and BSP threads leads to leaks and damage.

- Temperature and Environment — For high‑temperature environments or corrosive media, select stainless steel or specially coated fittings. In food and pharmaceutical applications, choose materials that meet hygienic standards.

- Vibration and Motion — In applications with vibration or movement, flexible hose with swivel fittings can prevent fatigue and leaks.

By following these guidelines, designers ensure that pneumatics maintain efficiency and reliability. Well‑selected fittings minimize maintenance and energy costs over the system’s lifetime.

Designing Pneumatic Systems — Control Strategies and Integration

To maximize the potential of pneumatics, engineers must integrate components into a cohesive system. This involves controlling valves and actuators, monitoring performance, and designing for energy efficiency and safety.

Control Architectures

Pneumatic control ranges from simple manual levers to advanced programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and distributed fieldbus systems. In manual systems, operators directly actuate valves. Mechanical cams or limit switches can automate simple sequences, such as clamping and releasing. For complex sequencing and coordination with sensors, PLCs or microcontrollers generate digital signals that drive solenoid valves. With the rise of Industry 4.0, smart pneumatics integrate sensors and communication modules to monitor pressure, flow and cylinder position in real time. Data gathered can predict maintenance needs and optimize performance.

Safety and Standards

Safety is a fundamental concern in pneumatics. Compressed air can produce unexpected motion if not properly controlled. Safety measures include:

- Lockout/Tagout procedures to isolate compressed air during maintenance.

- Pressure Relief Valves to prevent over‑pressurization.

- Safe Exhausting to remove trapped air before servicing equipment.

- Emergency Stop Valves that vent all air supply when actuated.

Standards such as ISO 4414 and EN 983 define requirements for pneumatic safety. Designing systems to meet these standards protects personnel and equipment.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability

Although pneumatics are less energy‑dense than hydraulics, there is growing emphasis on improving efficiency. Energy audits identify leaks, undersized lines and oversized valves. Pressure regulators set the minimum effective pressure, while flow control valves limit unnecessary consumption. Air blow‑off can be replaced by energy‑efficient vacuum systems or blow‑off nozzles. Heat recovery from compressors can provide facility heating. Smart monitoring systems detect leaks and provide maintenance alerts, ensuring that pneumatics contribute to sustainable operations. For example, the EB80 valve platform and FLUX digital flow meter track consumption and provide data for optimization.

Integration with Other Technologies

Pneumatic systems often interface with electrical and hydraulic systems. For instance, a machine may use electric stepper motors for precise positioning and pneumatics for clamping or part handling. Integration requires proper isolation, electrical controls must provide correct voltage to solenoid coils, and sensors may monitor cylinder position. Hybrid systems leverage the strengths of each technology: the speed and cleanliness of pneumatics, the precision of electromechanical drives and the high force of hydraulics.

In the era of automation and robotics, pneumatics play a supporting role by providing end‑effector motion, gripping objects and actuating safety systems. Recognizing how pneumatics integrate with vision, sensors and AI control will help designers create sophisticated systems.

Applications and Industries Leveraging Pneumatics

Pneumatics are ubiquitous across industries because they are safe, clean, economical and adaptable. Here are some key sectors where pneumatics make an impact:

Industrial Automation and Manufacturing

Automation lines rely heavily on pneumatics for tasks such as material handling, part positioning, pressing, stamping and packaging. Robots use pneumatic grippers for flexible grasping. Conveyors utilize rodless cylinders to move items along. Compressed air powers high‑speed pick‑and‑place operations and assembly sequences, making pneumatics indispensable for factories around the world.

Food and Beverage Processing

Because pneumatics do not leak oil, they are ideal for hygiene‑sensitive environments. Food production uses pneumatic cylinders to open and close valves, operate filling machines and position packaging. Automatic doors and conveyors move items through washdown areas. Clean air prevents contamination in beverages and dairy processing. The ability to withstand frequent washdowns and disinfectants makes pneumatics a cornerstone of food processing.

Medical and Dental Equipment

Pneumatic drills, scalers and dental chairs rely on compressed air to provide smooth and controllable movement. Hospitals use pneumatic systems for patient beds, ventilators and surgical tools. Since pneumatics avoid electrical sparks, they are safer near flammable anesthetics. The reliability and sterilizable nature of pneumatics make them essential in healthcare.

Automotive and Transportation

Air brakes on trucks and trains are classic examples of pneumatics. Automatic door systems on buses and trains use compressed air for smooth operation. Tire inflation, spray painting and power tools also rely on pneumatics in automotive repair and manufacturing. In packaging and automotive assembly, pneumatics handle routing of parts and pressing components together.

Construction and Heavy Industry

Tools such as jackhammers, nail guns and rock drills harness compressed air for powerful impact. Pneumatic tools are safer than electric tools in wet or explosive environments. Larger pneumatic cylinders operate gate valves, dampers and crushers. In mining, pneumatics actuate underground equipment where electrical spark hazards exist.

Consumer Products and Everyday Life

Pneumatics appear in everyday devices: vacuum cleaners, office chairs, basketball pumps and automatic garage door openers. The compressibility and power of air allow these products to operate quietly and reliably. In many households, pneumatics are unseen but integral to daily convenience.

By appreciating how pneumatics serve diverse industries, engineers can cross‑pollinate ideas and develop innovative applications.

Emerging Trends and Advanced Technologies in Pneumatics

Pneumatics continue to evolve with advancements in materials, sensors and digital integration. Several trends point to the future of pneumatics:

Smart and Connected Pneumatics

Modern pneumatics incorporate sensors to measure pressure, flow, temperature and cylinder position. These sensors feed data to controllers and cloud platforms, enabling predictive maintenance, energy optimization and quality monitoring. The EB80 valve system and FLUX flow meters illustrate the trend toward digital pneumatics: they provide real‑time data and integrate with plant networks for Industry 4.0 applications. Smart pneumatics help users identify leaks, reduce energy consumption and ensure consistent performance.

3D Printing and Custom Components

Additive manufacturing allows rapid production of bespoke pneumatic manifolds and valve blocks, reducing weight and size while optimizing flow paths. Complex shapes with internal channels can be printed in plastic or metal to streamline system design. 3D‑printed soft grippers actuated by pneumatics have emerged in robotics, enabling delicate manipulation of irregularly shaped objects.

Soft Robotics and Pneumatic Artificial Muscles

Soft robots use elastomeric bladders inflated by compressed air to create flexible movement. Pneumatic artificial muscles mimic biological muscles, contracting when pressurized. These technologies open new frontiers in assistive devices, medical robots and adaptive grippers. Pneumatics enable soft robotics to achieve safe interaction with humans and delicate objects.

Sustainable Air Systems

In pursuit of sustainability, engineers design air systems to recycle energy and reduce waste. Regenerative braking in pneumatic cylinders captures exhaust energy; compressors integrate variable speed drives and heat recovery; materials with low environmental impact are prioritized. Research explores replacing traditional oil‑lubricated compressors with oil‑free designs to improve air purity and environmental compliance.

Integration with Machine Learning

Machine learning algorithms analyze pneumatic sensor data to predict component failures and adjust operation parameters dynamically. By learning patterns of leakage and wear, AI‑enabled pneumatics can schedule maintenance proactively and adapt to changing process conditions. This level of intelligence brings pneumatics into the realm of autonomous systems.

These trends highlight a future where pneumatics remain relevant, combining the simplicity and cleanliness of compressed air with the intelligence and adaptability of digital technology.

Common Design Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even seasoned engineers can fall into traps when designing pneumatic systems. Recognizing these pitfalls can prevent downtime and inefficiencies.

- Undersized Tubing and Valves — Undersized lines restrict flow, causing slow cylinder speed and pressure drop. Always calculate flow requirements and select tubing and valves accordingly.

- Poor Air Quality — Contaminated air leads to sticking valves and cylinder wear. Installing proper filters, dryers and lubricators ensures reliability.

- Excessive Leakage — Leaks can consume significant amounts of compressed air. Regularly inspect connections, fittings and seals; use leak detection methods such as ultrasonic testing. Smart flow meters like FLUX can identify unusual consumption patterns.

- Inadequate Maintenance — Neglecting lubrication or failing to replace worn seals shortens system life. Develop preventive maintenance schedules and train personnel on proper upkeep.

- Ignoring Exhaust Air — Uncontrolled exhaust can generate noise and disturb nearby components. Use mufflers or silencing valves to reduce noise and direct exhaust safely.

- Overcomplicated Control — Complex valve logic may require unnecessary valves and tubing. Simplify control schemes using multi‑position valves or manifold assemblies to reduce plumbing and improve reliability.

By addressing these issues proactively, designers ensure that pneumatics operate smoothly and cost‑effectively.

Case Study: Designing a Pneumatic Pick‑and‑Place System

To illustrate how pneumatics come together, consider a pick‑and‑place system that transfers parts from one conveyor to another. The system uses two double‑acting cylinders for vertical and horizontal motion and a pneumatic gripper to hold the part.

- Requirements — The system must move a 2 kg part 300 mm horizontally and 150 mm vertically, cycle every 1 s, and operate in a clean environment. Speed is prioritized over precision.

- Cylinder Selection — Based on force calculations (F = P × A), a 40 mm bore cylinder provides sufficient force at 6 bar. Stroke lengths of 150 mm and 300 mm are chosen. Double‑acting cylinders allow controlled movement in both directions.

- Valves — A 5/2 solenoid valve controls each cylinder, providing independent exhaust and fast response. Flow control valves fine‑tune speed. The gripper uses a small double‑acting cylinder with a 3/2 valve to open and close.

- Air Supply and Preparation — A single compressor with a capacity of 800 L/min at 7 bar serves the system. Filters, regulators and lubricators condition the air. Pressure is set to 6 bar at the regulator.

- Control Logic — A PLC triggers the horizontal cylinder to extend. Once fully extended (detected by a magnetic sensor), the vertical cylinder lowers. The gripper closes to grasp the part, retracts vertically, retracts horizontally and releases the part. Sequence controls ensure smooth motion.

- Safety Measures — Pressure relief valves, exhaust silencers and emergency stop valves ensure safe operation. The system uses lockout valves for maintenance.

This example demonstrates how pneumatics deliver high‑speed, reliable motion with straightforward design and control.

Conclusion — The Enduring Power of Pneumatics

Pneumatics offer a compelling combination of simplicity, cleanliness, speed and affordability that continues to serve industry and everyday life. By understanding the core principles, advantages, cylinder options, valve types, fittings and design considerations, engineers and sourcing professionals can harness the full potential of pneumatics. The technology is evolving with smart sensors, additive manufacturing and AI, ensuring that pneumatics remain at the forefront of automation and human‑machine interaction. Whether you are designing a new production line or choosing components for a packaging machine, this comprehensive guide empowers you to make informed decisions about pneumatics.

As you embark on designing or upgrading pneumatic systems, remember to prioritize proper air preparation, select the right cylinders and valves, and consider environmental and safety factors. Embrace the possibilities of digital monitoring and intelligent control to optimize energy efficiency and performance. The world runs on compressed air, and with sound engineering and sourcing practices, pneumatics will continue to move machines and improve lives in the decades to come. If you’d like support selecting or sourcing reliable pneumatics components, feel free to contact us, we’re here to help.