Table of Contents

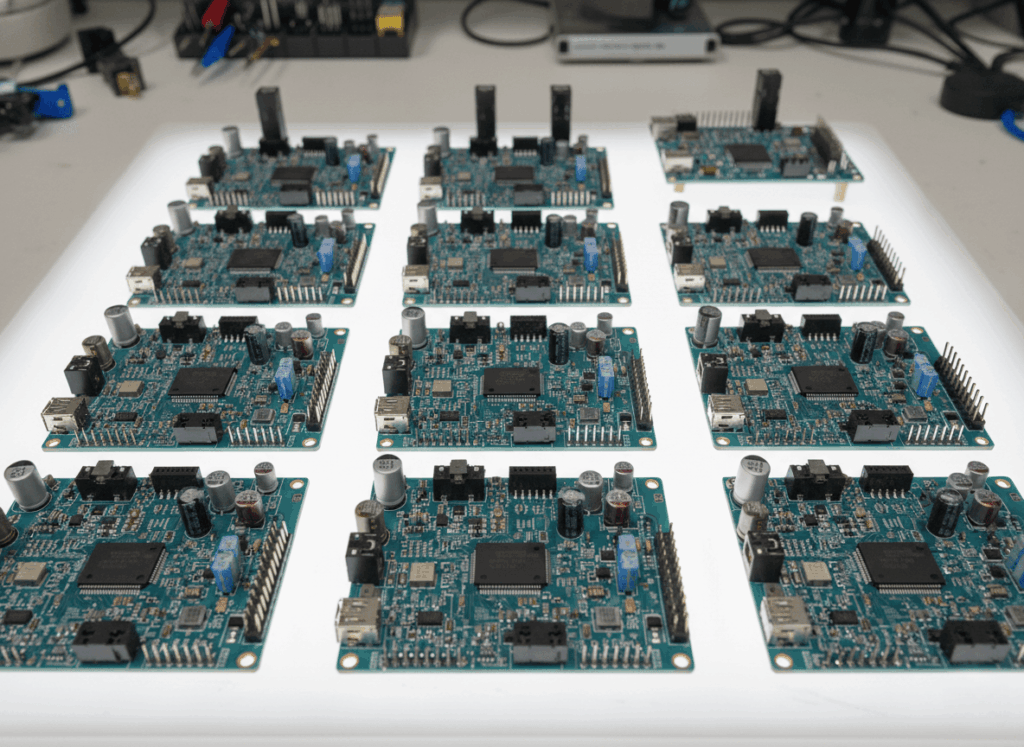

Printed circuit boards (PCBs) are the physical and electrical foundation of virtually every electronic device. If the individual components, microcontrollers, sensors, connectors and regulators, can be viewed as organs, then the PCB is the skeleton and circulatory system that holds everything together and distributes electrical energy and signals.

Without a properly designed and manufactured PCB, even the best components cannot function reliably. This article provides a comprehensive overview of PCBs and how to source them: from fundamentals like materials and stack‑ups to advanced manufacturing processes, performance considerations, quality standards, emerging trends and the role of a trusted partner such as Yana Sourcing.

Introduction — Why PCBs Matter

PCBs are more than mechanical supports; they interconnect components, provide stable ground and power planes, control electromagnetic interference (EMI), conduct heat away from hot devices, and define how a product will be assembled and tested. In the early days of electronics, circuits were built using point‑to‑point wiring, which was slow and error‑prone. The invention of the printed circuit transformed electronics into a scalable manufacturing discipline.

Today a PCB might be as simple as a single layer carrying an LED and a resistor or as complex as an eighteen‑layer board with high‑speed differential pairs, multiple voltage domains and embedded components. Even a four‑layer board contains multiple copper layers separated by dielectric; two outer layers handle most signal routing, while the inner layers serve as power or ground planes or additional signal layers. This layering improves signal integrity, reduces EMI and creates controlled return paths for high‑speed signals.

For consumer devices PCBs enable miniaturization; for automotive or industrial applications they ensure reliable communication between sensors and actuators under harsh conditions. Medical devices rely on PCBs for precision and safety. A poorly designed or fabricated PCB can compromise product functionality, reliability and compliance. Thus engineers, product owners and sourcing teams should understand PCBs in depth.

PCB Fundamentals — Stack‑Ups, Materials and Surface Finishes

A PCB consists of thin sheets of conductive copper laminated to an insulating substrate. The choice of substrate and copper thickness dictates electrical performance, thermal management and mechanical stability.

The most common PCB material is FR‑4, a composite of epoxy resin reinforced with woven fiberglass. FR‑4 offers high mechanical rigidity, flame resistance and superior insulation properties. Its epoxy–glass construction makes it highly resistant to heat, moisture and mechanical stress. Another advantage of FR‑4 is its high glass transition temperature (Tg); the material typically withstands 130–180 °C, which is vital for lead‑free soldering and high‑power applications. In addition, the epoxy resin provides excellent dielectric properties, making FR‑4 suitable for high‑frequency circuits where signal integrity matters.

Alternative substrates exist for specialized needs. Phenolic resin reinforced with paper, known as FR‑2, is inexpensive but offers low thermal stability and lacks flame retardancy. CEM‑1 is a hybrid substrate using a paper core and fiberglass reinforcement on the outer layers; it adds flame retardancy and moderate mechanical strength, but is limited to single‑sided boards due to the paper core’s inability to support through‑hole plating.

CEM‑3 uses a finer glass weave and a different epoxy formulation; it provides similar thermal and electrical performance to FR‑4 but at lower cost. High‑performance boards may use polyimide (flexible circuits), PTFE (low dielectric loss), ceramic (extreme temperatures) or metal cores (high thermal conductivity). The material choice affects cost, reliability and performance; selecting the right base ensures the board can handle mechanical stress, thermal cycling and electrical demands.

Layer count also influences performance. Single‑sided boards have copper on only one side and are used in simple circuits. Double‑layer boards add more routing capacity on the opposite side. Multi‑layer boards (four layers or more) provide ground and power planes that reduce noise and support high‑density routing.

A four‑layer stack, for instance, typically has signal layers on the outside and power/ground planes inside. More layers can separate analog and digital signals, reduce crosstalk and accommodate complex designs. Advanced designs use high‑density interconnect (HDI) techniques such as microvias and sequential lamination to achieve very fine trace pitches while keeping board thickness manageable.

Another important factor is the surface finish. Bare copper oxidizes quickly, making soldering difficult. Finishes such as hot air solder leveling (HASL), electroless nickel immersion gold (ENIG), electroless nickel electroless palladium immersion gold (ENEPIG), immersion silver and immersion tin protect copper surfaces and ensure solderability.

HASL is inexpensive but leaves an uneven surface; ENIG provides a flat surface and long shelf life but at higher cost; ENEPIG supports wire bonding; immersion silver/tin are mid‑range choices with shorter shelf life. The correct finish depends on the type of components, pitch, assembly process and cost considerations.

Performance Characteristics and Reliability

Electrical performance is influenced by impedance control, signal integrity, cross‑talk and attenuation. At high speeds, traces behave like transmission lines; their characteristic impedance depends on the dielectric constant of the substrate, trace width, spacing and distance to reference planes.

Controlled impedance traces (usually 50 Ω single‑ended or 100 Ω differential) require consistent geometry and materials. Using inner layers as solid ground and power planes in a four‑layer board improves impedance control and reduces EMI. For RF or 5G applications, designers may choose low‑loss laminates such as Rogers or MEGTRON.

Thermal and current considerations also matter. High‑current traces require wider widths or thicker copper to prevent excessive temperature rise. Boards intended for power electronics may use copper weights of 2 oz or more per layer, and incorporate thermal vias, heat sinks or metal cores to conduct heat away from hot components.

The board’s glass transition temperature must exceed the maximum reflow temperature and operating temperature; FR‑4 with Tg of 130–180 °C meets most requirements, while polyimide or ceramic may be necessary for extreme environments.

Mechanical reliability refers to the ability to withstand vibration, shock, and flexing without failure. Boards in vehicles, machinery or aerospace endure temperature cycles and mechanical stress. To prevent cracking or delamination, designers may incorporate strain relief features, avoid placing vias under connectors that experience repeated plugging/unplugging and use support ribs. The choice of laminate (e.g., high‑Tg FR‑4, polyimide) also contributes to mechanical robustness.

Testing and quality standards help ensure reliability. IPC standards define workmanship classes. Class 1 PCBs (general electronics) have basic requirements; Class 2 boards (service electronics) demand extended reliability; Class 3 boards (high reliability) require the highest standards and are used in medical, aerospace and military equipment. When sourcing PCBs for robotics or industrial automation, Class 2 or Class 3 may be appropriate. Quality checks include automated optical inspection (AOI), X‑ray inspection, flying probe tests and electrical continuity testing.

Design for Manufacture (DFM) and Design for Test (DFT)

Good PCB design must consider manufacturability. A design that is functionally correct might be impossible or expensive to fabricate if it violates process limits. DFM guidelines include using trace widths and spacing that the manufacturer can reliably etch; specifying drill sizes that can be accurately produced; avoiding annular rings that are too narrow; and keeping aspect ratios (board thickness divided by hole diameter) within acceptable limits. HDI designs may use microvias (small vias connecting only adjacent layers) but require careful planning to avoid stacking or overlapping microvias, which increases lamination cycles and cost.

PCBs designers must also choose among through‑hole vias, blind vias and buried vias. Through‑hole vias connect all layers and are the most economical. Blind vias connect an outer layer to an inner layer; buried vias connect inner layers only. These reduce routing congestion but add lamination steps and cost. Design for test (DFT) ensures the finished board can be efficiently tested. Adding test pads on key nets, accessible ground pads and connectors for boundary scan facilitate in‑circuit and functional testing. A board designed with DFT in mind reduces debugging time and increases yield in production.

Integration with Product Architecture

A PCB is part of a broader system. Mechanical designers must ensure that the board fits properly in the enclosure, aligns with mounting points and leaves space for connectors and cable routing. Thermal designers need to ensure adequate airflow and heat sinking. Electrical engineers must coordinate with power supply and EMI shielding design. For products with multiple boards (e.g., modules stacked or connected by flexible cables), the design must account for board‑to‑board connectors and harnesses. Collaboration among disciplines early in development avoids costly rework later.

Manufacturing Process and Sourcing Insights

Producing PCBs involve a multi‑step sequence. The design stage defines the layer stack, materials and via types. Material preparation involves cutting copper‑clad laminates and prepreg sheets to size. Inner layers are created by applying a photoresist, exposing the desired pattern to UV light, developing the image and etching away unwanted copper.

After the inner layers are etched, they are aligned with prepreg and outer copper sheets, pinned and laminated under heat and pressure to bond them together. Drilling creates holes for vias and component leads. The drilled holes are cleaned and then metalized by electroplating, connecting copper layers. Subsequent steps apply solder mask, silkscreen printing (component labels and logos), and the chosen surface finish.

When sourcing PCBs, buyers should evaluate manufacturers’ technical capabilities. Important metrics include minimum trace width and spacing, smallest drill size, ability to perform controlled impedance routing, capability for blind and buried vias, microvia expertise, and layer count capacity.

Material selection expertise matters in PCBs; some factories focus on standard FR‑4 while others handle advanced laminates. Certifications such as ISO 9001 and UL ensure that the factory has quality management systems and meets safety requirements. Minimum order quantities (MOQs) vary; prototype runs might be small (5–50 boards) while production orders could run to thousands. Lead times depend on complexity and volume; simple prototypes can be delivered in a few days, whereas multi‑layer boards with special materials may take weeks.

PCBs pricing is influenced by materials (FR‑4 vs. low‑loss laminates), copper thickness, number of lamination cycles, HDI features and inspection requirements. Low-cost quotes may hide compromises such as lower-grade material or relaxed quality criteria. Therefore, it’s important to review documentation, including stack‑up diagrams, material declarations and test reports.

Quality and Compliance

PCBs quality assurance encompasses both process control and final inspection. PCBs manufacturers use AOI to verify trace and pad dimensions against the design. X‑ray inspection reveals hidden defects under ball grid arrays (BGAs) and in vias. Electrical testing, either using flying probes or bed‑of‑nails fixtures, checks continuity and isolation. Solderability tests confirm that surface finishes accept solder. For mission-critical products, additional tests such as thermal cycling, vibration tests or humidity tests may be performed.

PCBs compliance with environmental regulations is mandatory for most markets. RoHS restricts hazardous substances such as lead and mercury. REACH regulates chemical substances used in manufacturing. UL certification, such as UL 94 V‑0 flame rating, ensures the board meets flammability requirements. Manufacturers should provide certificates of compliance and test reports. When exporting to Europe or North America, these documents may be required by customs.

Emerging Innovations and Future Trends

The PCB industry evolves continually to meet demands for higher performance, smaller size and lower environmental impact. High‑density interconnect (HDI) techniques allow for extremely fine trace widths and pitch, enabling modern smartphones and wearables. Flexible circuits (made of polyimide) and rigid‑flex boards (combining rigid and flexible sections) enable devices that fold or fit into irregular spaces.

Additive manufacturing and 3D printed PCBs are emerging for rapid prototyping and non‑planar designs. Embedded passives, resistors and capacitors built into the inner layers, reduce surface area and improve electrical performance. Eco‑friendly materials aim to reduce halogen content and improve recyclability. Meanwhile, advanced thermal management solutions include metal cores, heavy copper layers, heat pipes, and even microfluidic cooling channels. Optical PCBs, which integrate optical waveguides, promise high‑bandwidth data transmission for future communication systems.

Choosing the Right PCB Specification

Selecting a PCB specification balances performance, cost and risk. As explained in the PCB materials article, FR‑4 is the standard choice when mechanical strength, thermal stability and flame resistance are required. FR‑2 may be sufficient for low-cost, single‑sided boards not exposed to heat or moisture. CEM‑1 offers moderate cost savings with some flame retardancy, while CEM‑3 enables double‑sided boards with lower cost than FR‑4 but slightly reduced performance.

Beyond materials, other considerations include layer count, which must accommodate routing density and noise requirements; copper thickness, which affects current handling; and surface finish, which must match assembly processes. Designers must also choose via types and decide whether HDI is necessary. For high‑reliability applications, boards should meet IPC Class 3 or higher and include comprehensive testing. Cost per board generally increases with layer count, advanced materials and microvias, but the benefits may include improved performance and reliability.

Sourcing Verified PCBs with Yana

Navigating the global PCBs supply chain is complex. Partnering with a knowledgeable sourcing agent can mitigate risks. Yana Sourcing works with a network of ISO‑certified factories capable of producing rigid, flex, rigid‑flex and HDI boards. The team performs factory audits, verifies quality systems and reviews samples to ensure compliance with specifications. Technical specialists evaluate design files to recommend stack‑ups, materials and design improvements, and they match projects to suitable suppliers based on complexity and volume.

Yana provides more than price negotiation. It coordinates quality assurance through inspections and sample testing, verifies RoHS and REACH compliance, and manages UL marking requirements. Logistics support covers consolidation of shipments from multiple factories, customs documentation and optimization of shipping routes. Moreover, Yana monitors geopolitical developments, tariffs and supply chain disruptions, advising clients on risk mitigation and diversification. Because sourcing is a partnership, Yana emphasizes transparency, fair pricing and long‑term relationships; Yana’s ethos, “You Are Not Alone”, reflects a commitment to supporting clients from product concept through production scaling.

Conclusion

PCBs are the backbone of modern electronics, integrating electrical, mechanical, thermal and manufacturing considerations into a single platform. By understanding materials like FR‑4, CEM‑1 and CEM‑3, designers can choose substrates that meet performance and cost targets. Knowing how multi‑layer boards are constructe, through layer imaging, etching, lamination, drilling and plating, helps in planning realistic lead times and quality expectations. Controlling signal integrity, managing heat, designing for manufacturability and integrating testing are essential to reliability. Keeping abreast of emerging innovations like HDI, rigid‑flex and eco‑friendly materials ensures that products remain competitive.

The process of sourcing PCBs is about more than price; it requires technical insight, quality verification and risk management. A trusted partner like Yana Sourcing brings expertise across engineering, quality and logistics, turning a complex supply chain into a competitive advantage. By focusing on fundamentals and partnering with professionals, companies can build electronics that are not only functional but reliable, compliant and ready for the future.

If you’re planning a new build, scaling production, or revising your PCB architecture, we’d be glad to help. Reach out and tell us where you are in the design or manufacturing process.