Table of Contents

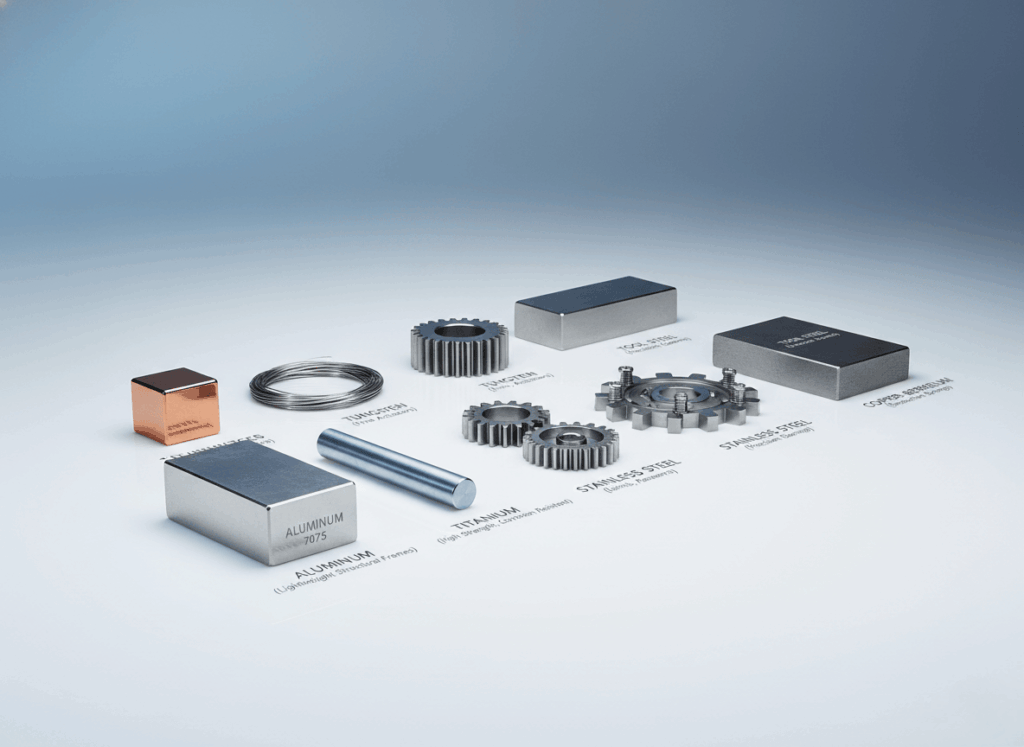

What Are Engineering Metals?

Engineering metals are metallic materials selected for mechanical design applications where strength, stiffness, manufacturability, durability, and predictable material behavior matter. Unlike commodity metals used for low-grade hardware or decorative purposes, engineering metals are defined by their structural performance and consistent material properties under load. They enable machines, robots, vehicles, tools, and industrial equipment to operate safely and reliably across long service lifetimes.

The value of engineering metals lies in their combination of strength and stiffness. Strength determines the load a material can carry without permanently deforming, while stiffness determines how much it deflects under load. Designs that require stable positioning, repeatable motion, or resistance to vibration depend heavily on the stiffness characteristics of engineering metals, especially in precision mechanisms such as robotic arms, linear slides, end-of-arm tooling, and machine frames.

Machinability also influences the selection of engineering metals, because parts must be produced with specific tolerances, surface finishes, and geometric accuracy. Some engineering metals can be milled, turned, or welded easily, while others require specialized tooling or heat treatment. Material processing affects both prototype development and scaled manufacturing, so choosing engineering metals with appropriate machining characteristics can shorten lead times and reduce production cost without compromising performance.

Another key factor is fatigue resistance, the ability of engineering metals to withstand repeated cyclic loading without cracking or failing. This matters in applications such as high-speed automation, robotic actuation, mechanical linkages, and rotating machinery where components may see millions of motion cycles. The fatigue strength of engineering metals directly influences system reliability and maintenance intervals.

This category is part of the broader framework of industrial materials discussed in the materials overview, where metals fit alongside polymers, elastomers, composites, ceramics, and magnetic materials. Understanding where engineering metals sit within that larger material family structure helps engineers compare alternatives and make informed decisions during mechanical design, sourcing, and optimization.

Core Families of Engineering Metals

Engineering metals cover a range of alloys, each with distinct mechanical and chemical characteristics that make them suited for different performance targets. Selecting among these families involves balancing factors like weight, corrosion resistance, hardness, machinability, and cost. Understanding how each group of engineering metals behaves allows engineers to match the material’s strengths to the mechanical and environmental demands of the application.

Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum alloys are lightweight engineering metals known for their high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and ease of machining. They are used widely in robotic arms, structural frames, and automation fixtures where reduced mass improves acceleration and efficiency. Grades such as 6061-T6 and 7075-T6 offer predictable mechanical properties and are compatible with anodizing for surface hardening and wear resistance.

Stainless Steels

Stainless steels are corrosion-resistant engineering metals that maintain mechanical strength in humid, chemical, or wash-down environments. They are preferred in medical robots, food-processing systems, and outdoor automation equipment. Austenitic grades such as 304 and 316 offer excellent corrosion resistance, while martensitic types (e.g., 420, 440C) provide higher hardness for precision shafts and bearing components.

Carbon and Alloy Steels

Carbon and alloy steels form the backbone of general-purpose engineering metals used in machinery, tools, and frames. They offer high tensile strength, good fatigue life, and predictable heat-treat response. Low-carbon steels are easy to form and weld, while medium- and high-carbon alloys like 4140 or 4340 deliver superior toughness and wear resistance for gears, spindles, and mechanical linkages.

Tool Steels

Tool steels are hardened engineering metals optimized for wear, impact, and heat resistance. They are essential in molds, dies, and cutting components that operate under high stress. Common types include D2, H13, and O1, each offering specific combinations of hardness and temperature stability. In automation, tool steels are used for press tooling, forming inserts, and gripper jaws that handle abrasive or high-pressure operations.

Titanium Alloys

Titanium alloys combine exceptional strength, corrosion resistance, and low density, making them premium engineering metals for high-performance systems. Their high stiffness-to-weight ratio benefits aerospace, medical, and mobile robotics applications where every gram matters. Despite their higher cost and machining difficulty, titanium components provide superior durability in environments where weight and reliability are equally critical.

Copper and Bronze Alloys

Copper and bronze alloys are conductive engineering metals used for electrical and thermal management, bearings, and wear surfaces. Copper’s high conductivity supports efficient current transfer in robotic sensors and grounding systems, while bronzes (like C93200 or C95400) provide self-lubricating characteristics ideal for bushings and sliding interfaces.

Magnetic and Soft Iron Alloys

Magnetic and soft iron alloys are specialized engineering metals used in motors, solenoids, transformers, and electromagnetic actuators. Silicon steels and soft iron cores enhance magnetic flux and reduce energy loss in high-frequency applications. Precision control of these materials’ magnetic properties allows modern robotic systems and automation devices to achieve smooth, efficient motion control.

Key Material Selection Factors

Selecting among engineering metals requires understanding how mechanical loading, environment, processing method, and production economics interact. The goal is not simply to choose the “strongest” or “lightest” material, but to find the engineering metals whose properties align with system requirements and lifecycle constraints. By evaluating strength, stiffness, corrosion resistance, machinability, and cost together, engineers can make informed and reliable design decisions.

Strength vs Weight

One of the most common trade-offs when selecting engineering metals is the balance between mechanical strength and mass. Heavy materials increase inertia, reducing the speed and efficiency of robotic arms and automation axes. Lightweight engineering metals such as aluminum and titanium enable faster acceleration and improved dynamic control, but may require thicker cross-sections or specialized fabrication to match the stiffness of steel. The ideal material is the one that meets load requirements while minimizing unnecessary mass.

Corrosion Resistance and Environmental Exposure

The operating environment strongly influences the suitability of engineering metals. Stainless steels and nickel alloys resist corrosion in washdown, marine, laboratory, or food-processing environments, while untreated carbon steels may degrade quickly under the same conditions. In outdoor systems, coastal facilities, or chemical handling equipment, the right choice of engineering metals prevents surface pitting, loss of structural integrity, and long-term maintenance issues. Matching material to environment is one of the most effective ways to maximize equipment life.

Machinability, Forming, and Heat Treatment

Different engineering metals offer varying degrees of machinability, formability, weldability, and heat-treat responsiveness. Aluminum alloys machine quickly and consistently, reducing fabrication time. Medium-carbon alloy steels like 4140 can be forged, machined, and heat treated to achieve specific hardness and toughness targets. Titanium and tool steels provide high performance but demand careful tooling, cooling, and finishing. Choosing engineering metals that align with available manufacturing processes reduces cost and shortens development timelines.

Cost, Availability, and Supply Chain Stability

Economic factors often determine whether engineering metals are practical for production. Materials with exceptional performance may carry high raw cost, require long lead times, or be vulnerable to supply fluctuations. In contrast, widely available engineering metals with standardized forms and well-developed machining data offer predictable procurement and maintenance advantages. The best selection balances performance with sourcing reliability, ensuring that the product can be produced consistently from prototype to full-scale deployment.

Considering Lifecycle and Maintenance Requirements

In high-cycle automation and robotics systems, the long-term durability of engineering metals is as important as initial performance. Fatigue resistance, wear behavior, and surface hardness determine how components behave after millions of cycles. Choosing engineering metals with appropriate treatment options, such as anodizing, nitriding, carburizing, or DLC coating, extends life and reduces downtime. Material selection is therefore not a one-time decision but part of a long-term reliability strategy.

Metals in Robotics & Automation

In robotics and automated machinery, engineering metals determine how a system moves, how efficiently it accelerates, and how long it maintains accuracy under repeated cycling. Because robotic systems are dynamic rather than static structures, weight, stiffness, fatigue resistance, and corrosion behavior all influence performance. Selecting the right engineering metals ensures the robot operates smoothly, with predictable precision and minimal maintenance.

Robotic Arm Frames and Structural Sections

Robotic arm frames require engineering metals with high stiffness-to-weight ratios so that the arm can move rapidly without excessive deflection. Aluminum alloys are commonly chosen to reduce moving mass while maintaining adequate rigidity. In applications demanding extreme strength or vibration stability, carbon steels or titanium alloys may be used to reinforce high-load joints. The choice of engineering metals directly affects acceleration capability, repeatability, and payload performance in multi-axis robotic systems.

End-of-Arm Tooling (EOAT) and Gripper Components

End-of-arm tooling benefits from lightweight engineering metals where mass reduction improves robot speed and reduces actuator effort. Aluminum and thin-walled stainless steel structures allow quick movement while maintaining structural integrity. In abrasive gripping or part-handling tasks, hardened tool steels or bronze alloys may be used for wear surfaces. The selection of engineering metals for EOAT balances rigidity, durability, mass, and interface geometry to achieve consistent, repeatable handling performance.

High-Cycle Linkages, Slides, and Joint Mechanisms

Components that experience continuous motion require engineering metals with excellent fatigue life and wear resistance. Alloy steels and tool steels are frequently used for linkages, pins, shafts, and cams where surface hardness and impact tolerance matter. In linear guide systems and sliding mechanisms, hardened bearing surfaces or surface-treated metals are used to maintain accuracy over millions of cycles. The right engineering metals reduce downtime and maintain smooth motion, even at high duty cycles.

Cleanroom, Medical, and Food Processing Automation

In environments requiring hygiene, sterilization, or chemical resistance, stainless steels become the preferred engineering metals. Grades like 304 and 316 resist corrosion, tolerate washdown, and maintain stability in humid or sanitary environments. Titanium may be used where both corrosion resistance and low weight are critical, such as compact surgical robots or precision laboratory automation. Selecting corrosion-resistant engineering metals prevents contamination and maintains compliance with safety standards.

Modular, Collaborative, and Mobile Systems

Collaborative and mobile robots often prioritize weight reduction and ergonomic handling. Lightweight engineering metals such as aluminum and magnesium alloys improve maneuverability and reduce energy consumption. For mobile platforms, where power draw directly affects battery life, the mass efficiency of engineering metals directly influences runtime and operational range. Choosing the right materials improves overall system efficiency and workload handling.

Surface Treatments and Performance Enhancement

Surface treatments allow engineering metals to achieve performance characteristics that the base alloy alone cannot provide. While the internal mechanical properties of engineering metals determine load capacity and stiffness, many applications require additional surface hardness, corrosion protection, friction reduction, or fatigue improvement. By applying the correct finishing or heat-treatment process, engineers can extend component life, enhance reliability, and maintain precision in long-cycle automation and robotics systems.

Anodizing (for Aluminum Alloys)

Anodizing is a controlled electrochemical process that increases surface hardness and corrosion resistance in aluminum-based engineering metals. Anodized surfaces also improve wear resistance in sliding assemblies and provide good adhesion for coatings or color finishes. In robotic end-effectors, anodized aluminum maintains strength while reducing mass, offering both structural efficiency and aesthetic consistency. Hard-anodized variants are used where abrasion and continuous motion are present.

Nitriding, Carburizing, and Induction Hardening (for Steels)

Heat treatments such as nitriding, carburizing, and induction hardening modify the surface layer of steel engineering metals to increase hardness and fatigue resistance while preserving core toughness. This combination is valuable for shafts, gears, cams, rotary joints, and linear motion components that operate under repetitive contact loads. By selectively hardening surface regions, engineers ensure that engineering metals maintain geometry and wear performance without becoming brittle throughout.

Passivation (for Stainless Steels)

Passivation enhances the corrosion resistance of stainless-steel engineering metals by removing free iron from the surface and improving the stability of the chromium oxide protective layer. This treatment is essential in washdown, medical, pharmaceutical, and food-handling robotics where material cleanliness and corrosion resistance directly affect safety and service life. Proper passivation maintains the performance of stainless steels without altering strength or dimensional properties.

PVD, DLC, and Low-Friction Coatings

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) coatings and Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) coatings transform the wear and friction characteristics of engineering metals. These coatings are widely used in linear guides, bearing surfaces, grippers, pinch rollers, and indexing mechanisms where smooth motion and long cycle life are required. Low-friction coatings reduce heat buildup, extend lubrication intervals, and maintain precision in applications where micrometers of wear would affect alignment or repeatability.

Why Surface Engineering Matters in Automation

Robotics and automation systems often run millions of cycles, meaning even minor wear or surface degradation can accumulate into performance drift. By combining correct base engineering metals with targeted surface enhancement, designs maintain accuracy, reduce downtime, and achieve longer service intervals. The surface is where most mechanical failure begins — treating it strategically is a core engineering advantage.

Material Comparison Tables (Copy-Paste Ready)

The tables below help engineers evaluate engineering metals quickly when balancing stiffness, weight, wear resistance, and fabrication requirements. These comparison tools are designed for early-stage concept evaluation and design reviews, where material decisions affect overall system performance, cost, and manufacturing approach.

Strength-to-Weight Comparison

(Higher = better for lightweight robotic structures)

| Material Type | Density (g/cm³) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Strength-to-Weight Performance | Typical Robotics Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Alloys (6061 / 7075) | 2.7 | 250–570 | High | Robot arm links, end-of-arm tooling frames |

| Stainless Steel (304 / 316) | 7.9–8.0 | 515–620 | Moderate | Food/medical automation frames, hygiene systems |

| Carbon/Alloy Steel (1018 / 4140) | 7.7–7.8 | 440–1100 | Moderate to High | Shafts, linkages, precision joints |

| Titanium Alloys (Ti-6Al-4V) | 4.4 | 800–1200 | Very High | Lightweight high-load robotic structures |

| Copper & Bronze Alloys | 8.5–8.9 | 200–450 | Low to Moderate | Bearings, heat spreaders, grounding systems |

Interpretation:

When reducing inertia in moving axes, engineering metals like aluminum and titanium offer meaningful acceleration and efficiency advantages.

Machinability and Fabrication Comparison

(Higher machinability = easier prototyping and lower production cost)

| Material Type | Machinability Rating | Notes on Fabrication Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Alloys | Very High | Clean cutting, low tool wear, excellent for CNC |

| Carbon Steels | High | Stable, predictable, wide heat-treat options |

| Stainless Steels | Medium | Work-hardens; requires correct feeds/coolant |

| Tool Steels | Low | Requires rigid setups and careful processing |

| Titanium Alloys | Low | Generates heat; requires sharp tools and control |

Interpretation:

Early prototypes often start in aluminum; heavy-cycle production transitions to heat-treated engineering metals when fatigue life matters.

Corrosion Resistance Ranking

(Higher = more suitable for washdown, outdoor, marine, chemical, lab, or medical environments)

| Material Type | Corrosion Resistance | Typical Protective Method |

|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steels (316 > 304) | Excellent | Passivation |

| Titanium Alloys | Excellent | Stable passive oxide layer |

| Aluminum Alloys | Good | Anodizing recommended |

| Carbon & Alloy Steels | Low | Paint, plating, nitriding, coatings |

| Copper & Bronze Alloys | Variable | May patina; sometimes desired |

Interpretation:

In sanitary or wet environments, stainless steel and titanium engineering metals maintain reliability with minimal maintenance.

Thermal and Environmental Suitability

(Higher = maintains mechanical performance across temperature and cycling conditions)

| Material Type | Heat Tolerance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tool Steels & Alloy Steels | High | Stable under shock and elevated temperature |

| Stainless Steels | High | Stable in high-heat + corrosive environments |

| Titanium Alloys | Moderate to High | Retains strength but costly to fabricate |

| Aluminum Alloys | Moderate | Strength decreases significantly with temperature |

| Copper & Bronze Alloys | Moderate | Better for conduction than structural load |

Interpretation:

Thermal exposure changes which engineering metals are appropriate — high-heat zones favor steels over aluminum.

Conclusion — Selecting Engineering Metals with Confidence

Engineering metals are foundational to mechanical design, automation systems, and robotics structures. Their strength, stiffness, fatigue resistance, and manufacturability determine how reliably a machine will perform under real operational conditions. By understanding the properties and trade-offs between aluminum alloys, stainless steels, carbon and alloy steels, tool steels, titanium alloys, copper-based materials, and magnetic alloys, engineers can make informed choices that directly improve system durability and performance.

In robotics and automation, the selection of engineering metals affects more than just mechanical strength—it influences cycle time, positional repeatability, maintenance intervals, and total system efficiency. Lightweight materials improve dynamic responsiveness, corrosion-resistant metals extend service life in washdown or cleanroom environments, and heat-treated or coated metals ensure stability under continuous cycling. Matching material behavior to real-world load cases prevents premature wear, drift, and performance degradation.

The tables and comparison frameworks in this guide support clear decision-making, allowing engineering teams to evaluate engineering metals not only by their inherent material properties, but by how they interact with manufacturing methods, environmental exposure, and product lifecycle requirements. A thoughtful material selection strategy leads to machines that run longer, require fewer rebuilds, and maintain accuracy over years of operation.

If you’d like support selecting or sourcing engineering metals for your robotics, automation, or manufacturing project, feel free to contact us, we’re here to help.