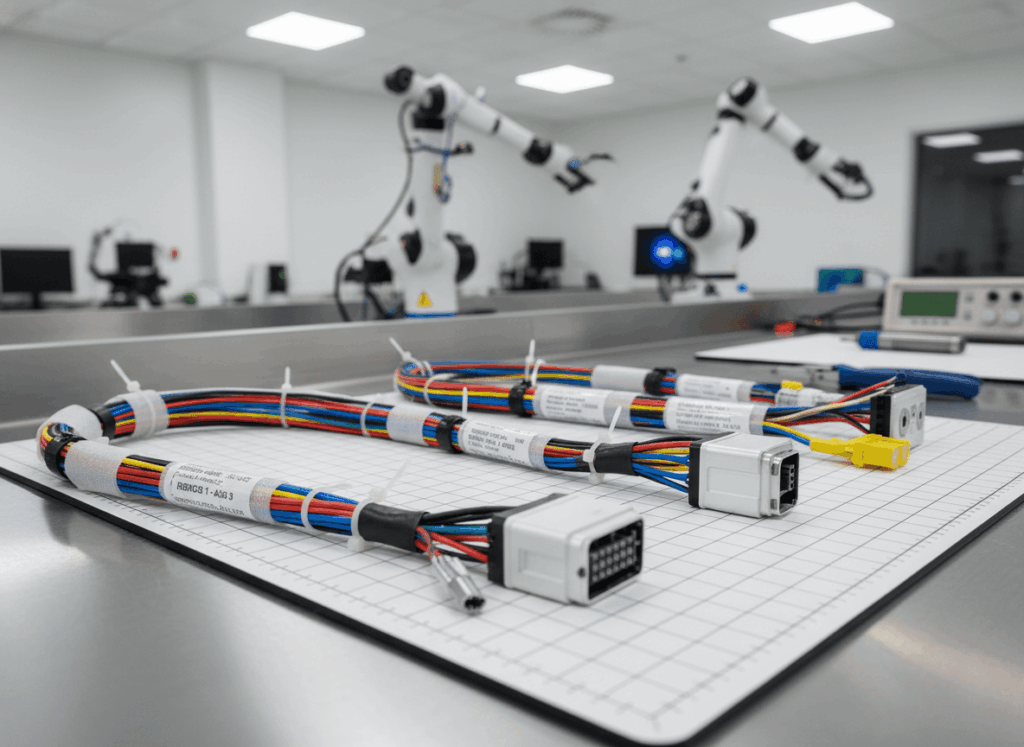

Wiring harnesses are the unsung heroes of modern electronics. When engineers marvel at a robot’s agility or a car’s electronics, they seldom think about the organized bundles of wires routing power and data through the machine. Yet these wiring harnesses determine whether a device functions reliably or falls victim to vibration, moisture, shorts or overheating.

A wiring harness, also called a cable harness, wire harness, wiring loom or cable assembly, is an assembly of electrical cables or wires that transmit signals or electrical power. The cables are bound together by a durable material such as rubber, vinyl, tape, conduit or braided yarn, turning a chaotic tangle of leads into a structured, manageable path. This article explores what wiring harnesses are, why they matter, how they are designed and produced, and how to source them responsibly. Whether you’re building robots, EVs, medical devices or consumer electronics, understanding wiring harnesses will improve your product’s performance and reliability.

1. Introduction — Why Wiring Harnesses Matter

Loose wires running between boards and modules might work in a lab prototype, but they quickly fail in real‑world products. Vibrations loosen connections; dust, oil and moisture cause corrosion; and wires can abrade against each other or the chassis. Wiring harnesses address these issues by bundling wires into a protective sheath. This simple act of bundling provides multiple advantages. Wiring harnesses secure cables against vibrations, abrasions and moisture.

By constraining wires into a non‑flexing bundle, space is optimized and the risk of a short is decreased. A single harness reduces installation time because installers connect one assembly rather than dozens of individual wires. Binding wires into a flame‑retardant sleeve also lowers the risk of electrical fires. For complex products like automobiles, aircraft and spacecraft, where kilometers of wire are common, wiring harnesses are the only practical way to maintain order and safety.

These benefits make wiring harnesses ubiquitous in industries beyond transportation. Consumer electronics use small harnesses to connect subassemblies; robotics relies on flexible harnesses that move with articulated joints; medical devices use miniaturized harnesses to route signals from sensors to processors. Because they affect assembly efficiency, serviceability and safety, wiring harnesses are strategically important. They may never be seen by end users, but their failure can lead to catastrophic results. Selecting appropriate materials, design methods and manufacturing partners is therefore critical.

2. Fundamentals of Wiring Harness Construction

At its simplest, a wiring harness is an assembly of insulated wires and cables bound together. Yet behind that simplicity lies a complex system of materials, processes and design choices. Each wire in the harness may have a different gauge (thickness) depending on the current it carries. Larger gauge wires handle higher currents without overheating; smaller wires support signals. Conductors are typically copper, chosen for its conductivity and flexibility. The conductors are insulated with various polymers—PVC for general purpose; XLPE or PTFE for high temperature; fluoropolymers like FEP for chemical resistance; or silicone for flexibility. The insulation must withstand operating temperatures, mechanical stress and environmental exposure.

The bundle is secured using binding materials. Cable ties, lacing cords or tapes hold wires together; fabric or self‑amalgamating tapes wrap branches; corrugated tubes and smooth conduits protect against abrasion; braided sleeves add EMI shielding and mechanical resistance. Harnesses often include heat‑shrink tubing at transitions or to provide strain relief. Over‑molded boots protect connectors and branch points from moisture and pull‑out forces. Within the harness, junctions are made by splicing wires, which may involve soldering, crimping or ultrasonic welding. Terminals such as ring, tongue, spade, flag, hook, blade, quick‑connect and offset connectors allow the harness to interface with other components.

Designing these fundamentals involves both mechanical and electrical engineering disciplines. Mechanical design considers the physical parameters: length, routing path, bend radius, mechanical stress, temperature extremes and environmental exposure. Protective materials like corrugated tubes, braided or silica sleeves are selected accordingly. Electrical design focuses on the logical, electrical and topological architecture: which wires carry power or signals, required operating ratings, shielding needs, and industry standards. Communication protocols and standards from organizations such as ASME, ISO and JASO influence wire sizing and harness topology. Thus, wiring harnesses are not generic commodities; each harness is engineered to meet specific mechanical and electrical requirements.

3. Performance and Reliability Considerations

The performance of wiring harnesses is multi‑dimensional, encompassing electrical integrity, mechanical robustness and environmental resilience. Electrically, harnesses must deliver the required current and voltage without overheating or excessive voltage drop. Designers calculate allowable voltage drop along the wire; choose wire gauges accordingly; and separate high‑current conductors from sensitive signal lines. Shielding may be required for signal lines to prevent electromagnetic interference (EMI). Twisted pair wires reduce crosstalk. Grounding strategies ensure noise does not propagate. The dielectric strength of the insulation must exceed system voltages to avoid breakdown.

Mechanically, wiring harnesses endure flexing, pulling and vibration. In static applications, harnesses may only need modest strain relief. In robotics, harnesses flex every time a joint moves; thus they must maintain integrity over thousands of cycles. Braided or woven sleeves provide abrasion resistance, while Teflon‑like insulations reduce friction. Harnesses used in doors or trunk lids must flex repeatedly; designers account for minimum bend radius to prevent conductor fatigue. Harnesses in engine bays must withstand high temperatures and chemical exposure; heat‑resistant insulations and heat shields become essential.

Environmental factors influence reliability. Moisture ingress can cause corrosion; temperature extremes can embrittle plastics. Harnesses may be exposed to oils, fuels, hydraulic fluids, salt spray or UV radiation. IP ratings help classify protection levels; for instance, an IP67 harness is dust‑tight and survives temporary immersion. Flame‑retardant sleeves reduce fire risk. Branch points are often sealed with epoxy or over‑molding to prevent moisture. Seal retention features are integrated into connectors. Additionally, wiring harnesses must resist rodent damage, especially in agricultural or industrial settings; the use of rodent‑resistant tapes or repellents may be necessary.

Reliability is also affected by human factors. Improper routing can lead to chafing; insufficient strain relief can cause wires to pull out of terminals. Mislabelled or color‑coded harnesses lead to assembly errors. Good practice includes using correct color codes, labeling wires clearly and providing identification sleeves at connectors. The harness design must allow enough slack for connectors to mate without excessive force while preventing loops that might catch on moving parts. Each of these considerations ensures that wiring harnesses deliver stable, long‑term performance.

4. Integration in Product Architecture

A wiring harness is not an isolated component; it must integrate seamlessly into the product’s mechanical and electrical architecture. On the mechanical side, designers must consider where the harness enters and exits the enclosure, how it routes within, and how it interacts with moving parts. Harnesses pass through bulkheads using grommets; these grommets prevent abrasion and seal against moisture. Routing channels or clips secure harnesses to the chassis. Designers often create 3D models of wiring harnesses to visualize clearances, bending radii and service paths.

Within the electrical architecture, wiring harnesses connect to printed circuit boards (PCBs) via board‑to‑board connectors or wire‑to‑board headers. The orientation of these connectors must allow harness exit in the desired direction while respecting board edge spacing and height constraints. The harness may connect multiple PCBs; careful mapping of pins prevents cross‑connections. For multi‑branch harnesses, designers decide where to split the main trunk into branches and which connectors go on each branch. The harness also interfaces with sensors, actuators, displays, switches and external power sources.

Integration includes serviceability. If a harness must be disconnected for repair or assembly, connectors should be accessible and keyed. Mis‑mating is avoided through mechanical polarization, color coding or keyed designs. Harness labeling is crucial; tags or printed sleeves indicate function and destination. Even small consumer products benefit from labeled harnesses; imagine trying to debug a mis‑wired control panel on a manufacturing line. Proper documentation, including harness drawings, termination charts and layout files, ensures that assembly workers and service technicians understand how to install and maintain the harness.

Finally, wiring harnesses must integrate with other interconnect technologies. Flexible printed circuits (FPCs) may bridge across moving joints; coaxial cables may carry high‑frequency signals; fiber optic lines may transmit data immune to EMI. A single product might use multiple harness types. The system architect decides which technologies to use where, balancing cost, performance and manufacturability. This holistic approach ensures that the harness contributes positively to the overall system.

5. Manufacturing and Sourcing Insights

Producing wiring harnesses is labour‑intensive. The process begins with design: engineers create a harness diagram showing wire lengths, routing, connectors and terminals. This diagram guides assembly on a pin board or workbench. Manufacturing typically involves the following steps:

- Wire cutting and printing: Wires are cut to length by specialized machines, often with wire marking printers that label the wire during or after cutting.

- Wire stripping: Machines remove insulation to expose the conductor ends for termination.

- Termination: The exposed ends are fitted with terminals or connector housings. Crimping is common; soldering is used for some applications. Ultrasonic welding may join wires.

- Assembly: Workers lay wires on a pin board according to the harness diagram and fasten them together with ties, tapes or lacing cords.

- Bundling: Protective sleeves, conduits or extruded yarn are applied over the bundle.

- Testing: The harness is tested for continuity and correct wiring using a test board that simulates the circuit. A pull test may measure mechanical strength and conductivity.

Despite automation advances, manual production remains common because many processes, routing wires through sleeves, taping branch points, crimping multiple wires, inserting sleeves and fastening strands, are difficult to automate. Manual assembly is often more cost effective, especially for low and medium volumes. Pre-production tasks (cutting, stripping, crimping and partial plugging of wires into connectors) can be automated, but final bundling and finishing typically require skilled workers.

From a sourcing perspective, the complexity of manufacturing influences lead times and MOQs. Standard harnesses may be available off the shelf, but custom harnesses, common in robotics, automotive and medical devices, require bespoke setups. Suppliers must prepare or purchase specific terminals, connectors and tools. The cost drivers include labour, materials (wire, insulation, connectors, sleeves), tooling for crimp terminals, quality testing and packaging. Suppliers may have MOQs for certain terminals; customizing connectors may require new molds. Delivery lead times vary from days (for small prototypes) to weeks or months (for complex harnesses with long lead components). A supply chain disruption, for instance, a shortage of a particular connector, can delay harness production and thus the entire product.

Working with experienced harness manufacturers mitigates these risks. Suppliers familiar with your industry can recommend alternative connectors or materials if standard parts are unavailable. They understand the importance of documentation, traceability and quality standards. They can also advise on design modifications that reduce labour or material cost without compromising performance. For global companies, local regulations and certification requirements must be considered; European harnesses, for example, need compliance with RoHS and REACH, while harnesses for export to North America may need UL or CSA approval. Yana Sourcing’s expertise in this area ensures that harnesses meet the necessary standards and are delivered on time.

6. Choosing the Right Wiring Harness for Your Application

Selecting wiring harnesses requires a balanced assessment of technical needs, environmental conditions, assembly processes and future maintenance. Begin by listing the electrical requirements: voltage levels, current per wire, signal types (digital, analog, high‑frequency), and electromagnetic susceptibility. Determine whether wires carrying high currents should be separated from sensitive signal wires to prevent heating and noise coupling. Choose wire gauges accordingly; consult standard current carrying tables. For signal lines, consider shielding; twisted pairs are beneficial for differential signals.

Next, evaluate the mechanical requirements. Will the harness flex or remain static? If the harness moves, design for bend radius and cycle life. Use stranded wires and flexible insulation. Will the harness pass through tight spaces? If so, keep the harness diameter small; choose thin insulation or consolidate wires in flexible printed circuits. Determine if the harness will be exposed to fluids, UV radiation, extreme temperatures or abrasion. For high‑temperature zones, select silicone or fluoropolymer insulation. For chemical exposure, use PTFE or polyurethane. For abrasion, protect the bundle with braided sleeves or corrugated tubes.

Consider the termination and mating requirements. If the harness connects to PCBs, specify connectors that align with board edge and orientation. If connectors will be mated and unmated frequently, choose terminals and connectors rated for high mating cycles and use gold or high‑quality tin plating. If connectors will be hidden or seldom accessed, you can accept lower mating cycle ratings and cheaper plating. Determine whether locking or latch mechanisms are necessary to prevent disconnection due to vibration.

Think about future maintenance. Use standardized connector families available from multiple suppliers. Avoid proprietary connectors unless necessary; they can lead to supply lock‑in. Label wires and branches clearly to aid troubleshooting and assembly. Plan for harness updates; design harnesses with spare circuits to allow future expansions or upgrades. For harnesses used in safety-critical systems, choose suppliers with quality certifications, such as ISO 9001 or IATF 16949, and ensure the harness meets applicable standards like IPC/WHMA‑A‑620 (discussed below).

Finally, work with your harness manufacturer early. Share your design files and performance requirements. Their experience can suggest design tweaks that improve manufacturability or reduce cost. They may propose pre-assembled sub‑harnesses, custom over‑molding or integrated grommets. In high volumes, automation may be viable; in low volumes, manual assembly is typically more economical. Aligning design and manufacturing early leads to successful harness selection.

7. Quality and Compliance

Producing reliable wiring harnesses requires adherence to quality standards. After assembly, harnesses undergo testing using test boards that simulate the circuit. The harness is measured for its ability to function in the simulated circuit. Pull tests measure mechanical strength and electrical conductivity when the harness is pulled against a minimum standard. Visual inspection confirms proper crimping and wire termination. High‑current harnesses may undergo thermal testing; high‑frequency harnesses may be tested for impedance and insertion loss.

In North America, the IPC/WHMA‑A‑620 standard defines minimum requirements for cable and wire harness assemblies. The standard covers electrostatic discharge protection, conduit, installation, repairs, crimping, pull-test requirements and other operations. It divides products into three classes: Class 1 for general electronic products where functionality is the main requirement; Class 2 for dedicated service electronic products requiring extended performance; and Class 3 for high‑reliability or critical applications. For wiring harnesses used in robotics or medical devices, Class 2 or Class 3 may be appropriate. Following these standards ensures consistent quality, reduces liability and eases regulatory approval.

European harnesses must comply with RoHS, which restricts hazardous substances like lead and cadmium. REACH regulates chemicals used in manufacturing. Automotive harnesses must meet USCAR standards, which specify tests for temperature, vibration, corrosion and electrical performance. Aviation harnesses must satisfy MIL‑DTL or ARINC standards. Medical harnesses must adhere to ISO 13485 for quality management and sometimes IEC 60601‑1 for electrical safety. In addition to product-specific standards, harness manufacturers should implement quality management systems (ISO 9001) and environmental management systems (ISO 14001). Traceability procedures allow manufacturers to track materials and processes; if a defect arises, the affected batches can be identified and corrective actions implemented.

8. Emerging Innovations and Future Trends

The world of wiring harnesses is evolving rapidly. One prominent trend is the shift toward digital design and manufacturing. Harness design tools now integrate 3D modeling and routing with electrical schematics; engineers can visualize harness routing within the mechanical assembly, avoiding collisions and optimizing lengths. Simulation tools predict electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), signal integrity and voltage drop. These digital tools reduce errors and expedite design revisions.

Automation is another innovation. Although manual assembly remains common, certain operations are becoming more automated. Smart machines can cut, strip and crimp wires with minimal human intervention. Automated testing machines can load harnesses into test fixtures and run electrical tests while recording results. Some facilities use robots to route wires through conduits or insert terminals into housings. However, human dexterity is still unmatched for complex harnesses.

New materials are emerging. Lightweight aluminum wires reduce mass in vehicles, improving fuel efficiency. High‑temperature plastics allow harnesses to operate near engines or in industrial ovens. Conductive polymers enable flexible printed conductors integrated into harnesses. Self‑healing insulation repairs small cuts or abrasions. There is also growing interest in recyclable and bio-based plastics to reduce environmental impact.

Another trend is the incorporation of data and intelligence into harnesses. Some harnesses include embedded sensors that monitor current, temperature or strain, providing predictive maintenance data. Others integrate identification chips that inform the control system about the harness type and configuration. Modular harness architectures allow harnesses to be assembled from standardized segments, enabling faster customization and repair. In robotics and IoT devices, harnesses may include fiber optic segments for high‑bandwidth communication immune to electromagnetic interference.

Finally, additive manufacturing opens new possibilities. 3D printing of wiring harness supports, clips and protective covers enables complex shapes tailored to specific enclosures. Future harnesses might use printed conductors embedded in flexible substrates, eliminating discrete wires altogether. Although these technologies are nascent, they promise to change how wiring harnesses are conceived and produced.

9. Sourcing Verified Wiring Harnesses with Yana

Navigating the global supply chain for wiring harnesses can be daunting. Yana Sourcing offers a higher‑dimensional approach that combines technical insight with supplier management and logistics. Instead of merely acting as an intermediary, Yana evaluates your project, helps specify the harness requirements and identifies manufacturers whose capabilities align with your needs. The team reviews your harness drawings, pinouts and operating environment. They advise on wire gauge, insulation materials, shielding and branch protection. They also check that the harness design follows mechanical and electrical guidelines and relevant standards.

Yana’s supplier network is vetted for quality certifications and process control. The suppliers have experience with automotive, industrial, medical and consumer harnesses. Yana audits them for compliance with IPC/WHMA‑A‑620, RoHS, REACH and industry‑specific standards. During production, Yana monitors cutting, stripping, crimping and assembly operations and ensures that manual steps are performed correctly. They review test results from electrical and pull tests and perform random inspections. This thoroughness reduces the risk of harness failure in your product.

Another advantage of working with Yana is supply chain resilience. If a particular connector or wire becomes scarce, Yana can propose alternatives and coordinate design changes. They consolidate shipments from multiple harness manufacturers, reducing freight cost and customs complexity. Yana also manages project timelines, ensuring that harnesses arrive when needed to support assembly schedules. Through clear communication and transparency, Yana builds trust and reduces stress for your engineering and procurement teams.

10. Call to Action — You Are Not Alone

The process of sourcing wiring harnesses is about more than price; it requires technical insight, quality verification and risk management. A trusted partner like Yana Sourcing brings expertise across engineering, quality and logistics, turning a complex supply chain into a competitive advantage. By focusing on fundamentals and partnering with professionals, companies can build electronics that are not only functional but reliable, compliant and ready for the future. If you’re developing a new harness, resolving reliability issues or scaling production, we’re here to help. Share your drawings, photos or even napkin sketches, and we’ll help you turn them into clear, manufacturable wiring harnesses. Contact Yana Sourcing.